LUCAS REINER

Lucas Reiner has been exhibiting internationally since 1993. Over the past three decades he produced several notable series of chromatically variegated paintings reflecting his perennial inspirations (contemporary urban trees, pyrotechnic explosions, traditional spiritual themes) in a range of media (including oil, acrylic, tempera, watercolor, drypoint etching, monoprints, and photography).

Born in 1960, Reiner attended the Parsons School of Design and The New School for Social Research in New York, Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles, and the Parsons School of Design in Paris.

His recent solo exhibitions include: A Requiem in Progress (2023) a solo exhibition at Studio La Citta, Verona, Italy, The Stations of the Cross (2023) exhibition of paintings and etchings at The Athenaeum Center for Thought and Culture, Chicago and group exhibitions at Frederick R. Weissman Museum of Art at Pepperdine University, Galerie Born in Berlin and Dars, Germany, Alloft gallery in Connecticut, and Solway Gallery in Ohio.

In 2019, Reiner began exhibiting several large-scale paintings at Galerie Nordenhake in Berlin, Germany. A solo exhibition of Reiner’s paintings titled Himmelsleiter was presented by Galerie Biedermann in Munich, Germany, in 2017. His work was also included in the 2018 exhibition titled Dos Colectivos presented by the University of California’s Fisher Museum of Art (Los Angeles), Instituto de Artes Gràficas (Oaxaca) and Nacional de la Estampa, Mexico City. A monograph of Reiner’s work titled Los Angeles Trees was published in 2008 featuring work produced over several years that examines the formal collision between organic growth and the harsh strictures of urban life embodied by trees lining city streets. Selected by The Los Angeles Times as one of its “Favorite Books of 2008,” Reiner’s paintings, drawings, and photographs of trees were characterized by writer Susan Salter Reynolds as “exuberant, determined, and whimsical…[Reiner’s] trees exude patience and humor.”

In 2008 upon invitation to produce a Stations of the Cross for St. Augustine’s Episcopal Church in Washington, D.C. and in the wake of his mother’s death, Reiner embarked upon a series of watercolor studies, subsequently working with the German master printer Clemens Büntig Editionen to produce a limited edition of etchings. Over the next seven years, this body of work (known as The Stations Project) culminated in fifteen large-scale paintings evoking the timeless path of transformation through contemplative visual space. Transcending religious affiliation, these works engage the profound capacity of art to embody the universal human longing to comprehend suffering, loss, and the passage of time.

Reiner’s work is represented in museum collections worldwide, including: Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Staatlichen Graphischen Sammlung (Munich, Germany), Diözesan Museum (Freising, Germany), Colecciòn Jumex (Mexico City, Mexico) and the American Embassy Collection (Riga, Latvia), among others.

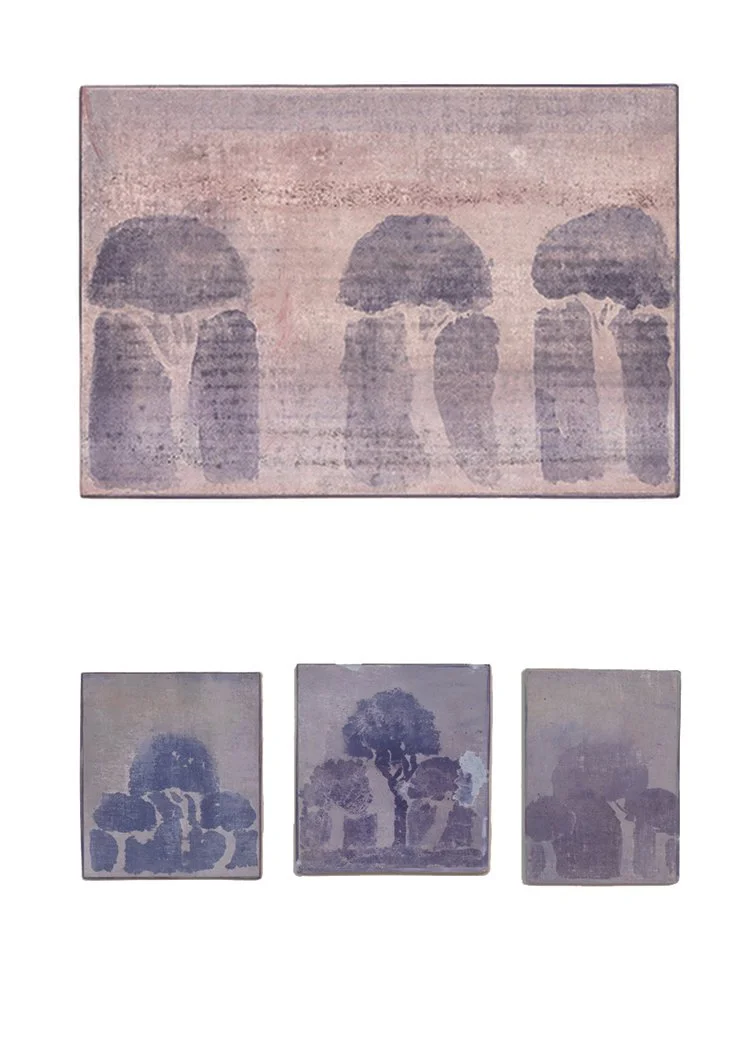

Top image: Inglewood, Nutwood Ave. #1, 2016, Tempera on muslin on wood, 8 5/8 x 12 1/2 “ Bottom images: 1. Inglewood, N La Brea Avenue #1, July 27, 2016 Tempera on muslin on wood 8⅝ x 7⅝”

2. Inglewood, N La Brea Avenue, April 30, 2020 Tempera and house paint, pencil, on muslin on wood 8 x 8⅛” 3. Inglewood, N La Brea Avenue, 2016 Tempera on muslin on wood, 10⅛ x 6”

INGLEWOOD CATHEDRAL

As a native Southern Californian, throughout my life, the ‘Fabulous’ Forum in Inglewood has always been a ‘Temple’ of sports and music, where I heard and saw everyone from Led Zeppelin to the Lakers. Now, the stunning spaceship, So-Fi Stadium has arrived as another place of worship, but it is the trees of Inglewood that continue to beguile me and hold my interest.

The paintings of Inglewood trees in Inglewood Cathedral, represent a naive proposal; what if the trees that line our streets, and in fact all of nature, were to be seen and felt in our minds as sacred? The archway, commonly employed by architects to demarcate the transition from a mundane exterior space to a sacred interior, can be seen in Inglewood as a canopy of trees providing not only shade and oxygen, but also a passageway to a profound moment of mystery for those open to feeling it.

A painting too can be a kind of passageway to a sacred place. With the Inglewood Cathedral paintings, I wonder, and hope, the reverence we have for art can be extended to all that surrounds us. As we step under their unassuming branches, what if the cathedral begins here, on North La Brea Ave., on Centinela Ave, on La Cienega Blvd?

– Lucas Reiner, Los Angeles, 2023

Inglewood Cathedral - Lucas Reiner

by Shana Nys Dambrot

The groves were God’s first temples. — William Cullen Bryant

The heady sensation of horizons expanded, roots rediscovered, the dance of the strange and familiar, old and new—it’s an archetypal tale of travel and inspiration. As painter Lucas Reiner admired the majestic trees flanking Ferraro, Italy’s San Benedetto church, his mind and eyes fresh from the glow of an exhibition of Chardin paintings, he noticed their domed coiffures and cathedral-like rise of archways and filtered light. He spent time with them, photographed them, and in 2010 made a suite of 67 monoprints inspired by them. Later, outside the Inglewood studio where he’s worked since 2011, Reiner came to see that his neighborhood’s trees held the same shapes, and the same power.

That Reiner would focus on trees is not a surprise—and not just any trees, abstracted or generalized, but specific, individual trees, as unique as people and remembered in the same way. Urban trees have been a recurring subject in his work for decades. He jokes that people still alert him to particularly eccentric trees around the city, particularly those who have suffered the ungentle, anti-aesthetic touch of city maintenance workers. It’s something of a miracle that the trees which inspired Inglewood Cathedral have thus far escaped the more violent impact of civilization on trees. Reiner also undertook a series of paintings based on the Stations of the Cross, with trees enacting the emotional tableaux. He’s been further interested in post-abstraction strategies for provoking the psyche in the absence of narrative; he thinks a lot about Rothko’s ideas on distillation and “personal icons” and what constitutes devotion.

The diaphanous, penumbrous paintings in Inglewood Cathedral represent a synthesis and evolution of all these ideas—formal, material, art historical, philosophical, spiritual. What if trees were treated as the radiant and sacred beings which they are. What if such trees are the real cathedral, whether on North La Brea Ave. or in a piazza in Ferraro, or anywhere and everywhere. What if the Old World and the New World swapped places, and Caspar David Friedrich stood in nature but looked inward toward his soul. What other mysteries would an elevated quality of attention reveal to us about the world. Why does nearly every spiritual tradition and human-dreamed cosmology have a story about a tree. What formal and material techniques are available to an artist to express the glory of the overlooked.

To give these esoteric ideas concrete form, Reiner renders trees with the patient attention of portraiture, employing a lexicon of architectural materials and evocative facture that infuses the works with an object quality that’s as much holy relic as contemporary abstract—like burial shrouds or the rough stones of an ancient wall. In some ways the trees themselves are performing architecture in their form and effect, creating a liminal space for transporting from the mundane to sacred, unifying a duality. Muslin is backed with a mixture of gesso and marble dust, which is pressed through its weave to form grounds with a mottled surface; the tempera is forced to find its own level across this topography. Like that paint and those trees, humans too must always adapt to the circumstances in which we find ourselves; neither we nor the trees choose where to be planted. But also like the trees, we are a radiant and sacred part of nature, and we would do well to remember this no matter where we find ourselves.

— Shana Nys Dambrot, Los Angeles, 2023